| |

|

|

Short-Time Work

|

|

|

The German Answer to the Economic Crisis |

PDF Download

The reaction of the German labor market

to the worst global recession in postwar

history was relatively mild. It has

so far not translated into a significant

employment decline. Quite the contrary,

the size of the German working population

remained at a record level of more

than 40 million people through both

2008 and 2009. Short-time work certainly

made a substantial contribution

to this astonishing development. The

instrument helped significantly to cushion

layoffs by extending subsidies for a

temporary reduction in working hours.

A recent study by IZA Director Klaus F.

Zimmermann, IZA Research Associate Ulf

Rinne and Karl Brenke (DIW Berlin) analyzes

how short-time work has developed

and where in the economy it is

especially common, in particular

during the latest economic

crisis. Short-time work was, and

is, especially common in Germany’s

industrial sectors which

rely heavily on exports as well

as those service sectors closely

linked to industrial production.

At the end of 2009 one in

six employees with jobs subject

to social security contributions

and employed in machine construction

and metal production

worked reduced hours; in the

automobile industry it was one

in seven. As the number of short-time

workers declines, the proportion

of those who had long

since had their regular working

hours reduced is growing. Therefore, the

indications are that a base of long-term

short-time workers is developing.

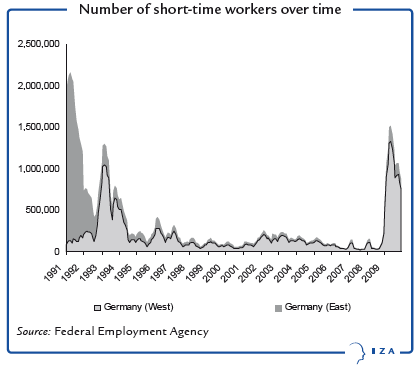

A look back in history

The origins of a specified payment made

to employees in the case of short-time

work can be dated to the beginning of the

last century. The precursor was a law on

amendments to tobacco tax in 1909, as

a rise in tolls and taxes would mean less

work in the tobacco processing plants.

After World War I, short-time work was

integrated into the newly created unemployment

benefit scheme in all sectors

of the industry. Short-time work was deployed

on a massive scale during the f irst

economic crisis of the Weimar Republic.

By the time the world economic crisis

peaked in 1932, the share of short-time

workers had increased to more than

20 percent.

|

|

Regulations governing short-time

work during the time of the Weimar

Republic were broadly adopted by the

Federal Republic. Short-time work was

again deployed on a large scale in the

second half of the 1960s, which witnessed

the first post-war economic

crisis. After little over a year, however,

short-time work had once again

disappeared and unemployment had

greatly declined. Another vigorous rise

in short-time work in the middle of the

1970s and the first half of the 1980s

resulted from the oil and energy crises.

German reunification presented a

special case. Following the monetary,

economic and social union, production

in the former German Democratic

Republic collapsed at lightning

speed, and underemployment drastically

increased. Initially, the response

was predominantly the deployment of

short-time work. In the

beginning of 1991, more than a quarter

of all employees in East Germany were in

short-time work. The reduction in working

hours was often as much as 100 percent.

On the one hand, the wish was to

retain the workforce because it frequently

represented the intrinsic essence of the

firms, with a view to privatization; on the

other hand, the soaring rise in unemployment

was supposed to be kept in check.

This backdrop, therefore, meant that

short-time work was widely used, since

time was needed to conceive, then introduce,

other labor market policy instruments

to create jobs, and encourage further

education and retraining. As these

became available, the number of short-time

workers in East Germany drastically

declined. Hence, short-time work at that

time did not serve as an instrument

to bridge a temporary production

gap but as first aid to

help cushion the social shock of

the economic upheaval.

A short while later, following the

end of the reunification boom,

the number of short-time workers

once again increased – this

time, however, primarily in West

Germany. In the two periods

of economic downturn which

were to follow (1996/1997 and

2001/2004), short-time work, in

contrast, increased relatively little

although unemployment rose

steeply.

Short-time work during the crisis

Even so, in the recent economic crisis

short-time work was applied more extensively

than ever before in the history of

the German Federal Republic following

the upheaval of reunification. Amendments

to laws and regulations certainly

made a substantial contribution. The

number of short-time workers drastically

increased from October 2008 and peaked

in the second quarter of 2009. In May

2009 more than 1.5 million employees

received the short-time work allowance

due to economic reasons. In December,

the month for which there is the most recent

data, this figure still stood at more

than 800,000. The question how much of

the reduction in short-time work can be

attributed to dismissals or a reduction of

work capacity

within the company cannot

be answered due to the scarcity of

information. Unemployment would

have undoubtedly risen much more

steeply – in absolute terms around

twice as much as it actually had

grown from the middle of last year. In

addition to the decrease in the number

of short-time workers, the actual

figures regarding the development of

employment and unemployment also

indicate more of a loosening rather

than a tightening of the labor market.

|

|

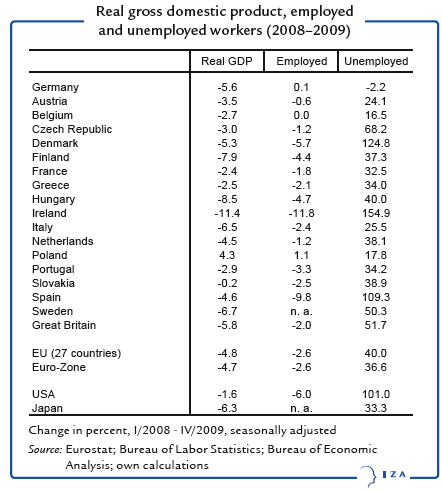

Short-time work is clearly one of the

key reasons why the Germany labor

market has remained largely unaffected

by the massive drop in production

that has hit the economy in

the spring of 2008. In other industrial

countries the impact of the crisis

was much stronger: In the United

States or Spain, for instance, unemployment

more than doubled while

the German rate remained nearly

constant.

Manufacturing particularly affected

With regard to different sectors,

there are also large differences

in the extent of short-time

work as a consequence of

the recession. While before the

economic crisis short-time work

could also be found to a considerable

degree in the construction

industry, the main emphasis

shifted to the manufacturing

sector during the course of the

crisis. In the middle of 2009, this

sector accounted for four-fifths

of short-time workers. However,

not only did f irms in manufacturing

determine the rise of

short-time work, they also governed

its fall. The development

of short-time work in other sectors

generally proceeded less

dynamically.

Nonetheless, the effect of short-time

work on this sector has

been far greater. The reason for this was

that the crisis in Germany had so far been

felt mainly in the form of a drastic decrease

in foreign demand, and the export industry

is driven in particular by firms in the

manufacturing sector. At the end of 2009,

one in ten employees subject to social security

contributions were receiving short-time

work allowance due to a reduction of

working hours in light of the economic situation.

This proportion was much lower in

every other sector.

A survey of the individual sectors reveals

a more diverse picture: short-time work

was widespread within the manufacturing

sector, in particular in engineering, metal

construction and car manufacturing – all

of which are export-oriented industries.

The same goes for textile manufacturing.

In comparison, short-time work was

used less extensively in sectors which cater

more for the domestic market. Thus,

the share of short-time work in the food

industry was a mere 0.3 percent at the

end of last year. Furthermore, not every

export-oriented industry had to extensively

adopt short-time work. One example is

the pharmaceutical industry, whose turnover

is generally less dependent on fluctuations

in the world economy: this sector’s

rate of short-time work was 0.8 percent.

|

|

|

A relatively large number of short-time

workers are to be found in areas of the

service sector in which a considerable

share of the activity is of an industrial nature

− such as the transport sector and

wholesale trade, engineering services,

advertising and temporary employment

agencies. Others sectors also include IT

services and consulting. There are, however,

sectors in the service industry in

which there is no discernible reason for

the reduction in work hours. They should

not have been affected, either directly or

indirectly, by the weak foreign demand.

Some of them, such as retail trade, hotels

and restaurants, and travel agencies, are

geared towards domestic consumption;

and domestic demand in Germany had

remained stabile despite the economic

crisis. In the construction sector, the extent

of short-time work supposedly put

down to the economic circumstances is

surprisingly high, even though production

in this sector increased significantly

from the middle of 2009 and a seasonal

short-time allowance for loss of working

hours due to weather conditions is available.

Other sectors of the economy, such

as public administration, education and

teaching, as well as health care and social

services, are by and large not sensitive to

economic circumstances – nevertheless,

short-time workers can also be found

here. It may be that these sectors have

resorted to short-time work not because

of economic circumstances but more because

of internal difficulties or structural

problems. |

|

Prolonged short-time work

Prolonged short-time work

The average loss of hours for each short-time

worker has changed little since the

middle of 2009; in the past this average

had risen significantly during the

expansion phase of short-time

work. In December 2009, 60

percent of short-time workers

had working hours reduced by

up to a quarter of their contractual

obligation. As few as

one in ten had their normal

working hours reduced by

more than a half. The average

loss of hours amounted to

nearly 30 percent. Since 3 percent

of all employees subject

to social security contributions

were involved in short-time

work at the end of 2009,

the reduction of their working

hours accounts for less than

1 percent of the contractually

obligated work volume.

Whilst the total number of

short-time workers fell, the

share of employees who had experienced

a loss of hours over a

prolonged period of time rose

considerably. By the end of 2009 three

quarters of short-time workers (more

than 600,000) had been working short-time

for more than six months, 85,000

for even more than a year. The structure

of these time periods indicates that it is

leading to a structural hardening and the

establishing of a base of long-term short-time

workers. This form of long-term unemployment

is predominantly found in

manufacturing, especially in the metal

sector such as engineering and the automobile

industry.

Consequences and policy responses

Short-time work is an instrument which

can be utilized by firms to react flexibly to

changing economic circumstances. In periods

in which the economy is struggling,

the social blow of lost working hours can

be cushioned; and when the situation

improves, the necessary personnel are

immediately available. It was therefore

right to make the regulations governing

short-time work more attractive to those

affected by the crisis. In this manner, a

rise in unemployment was prevented. The

vigorous adoption of the short-time work

regulations during the crisis is proof of

the success of this policy.

It must be kept in mind, however, that

short-time work only represents an instrument

for the temporary stabilization

of the labor market: in the medium

term, negative effects can also appear.

Hence, firms could be tempted by the

possibility of longer implementation of

short-time work to neglect the necessary

efforts for improvement: in particular,

improvements in competitiveness and focusing

on new market conditions which

also require adjustments to the structure

and scope of the personnel. Therefore,

policymakers should be contemplating

an early exit out of the current rules governing

short-time work.

|

|

|

The discussion,

however, has

mainly concentrated

on conflicting suggestions:

instead of

considering possible

scenarios for

a phasing out of

short-time work,

politicians are

currently considering

the idea of

once again increasing

the eligibility

period for

the short-time

work allowance.

Furthermore,

social security

contributions

for short-time

work are not to

be paid by the

employers from

the beginning of

2011, as was planned, but will continue

to be reimbursed by the Federal Employment

Agency. Collective wage bargaining

agreements, which, in the case of short-time

work over a longer period, both

parties can bear a greater portion of the

costs than before, are possibly more efficient than these legal specifications. In

this way, incentives to refrain from making

the necessary structural adjustments

can be avoided.

|

|

|

There is the danger with all forms of

state intervention associated with cash

benefits or other instruments (such as

transfer payments, tax breaks or subsidies)

that they are open to abuse or lead

to deadweight losses. This also seems to

be the case with short-time work. Thus,

short-time workers are also to be found

in sectors not confronted with a loss of

working hours primarily due to economic

conditions. A narrower interpretation

and a consistent application of the laws,

together with tighter controls, could

overcome some shortcomings. With this

in mind, an institutionalizing of the extension

period for short-time work is unadvisable,

as misapplication can never be

completely avoided.

|

|

Wochenbericht des DIW Berlin 16/2010, 2-13

Wochenbericht des DIW Berlin 16/2010, 2-13

Kurzarbeit: Nützlich in der Krise, aber nun den Ausstieg einleiten

Karl Brenke

Ulf Rinne

Klaus F. Zimmermann

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|