| |

|

|

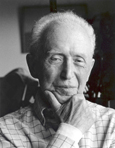

In Memoriam: Jacob Mincer (1922-2006)

|

|

|

| | Jacob Mincer |

Jacob Mincer, the first winner of the IZA Prize in Labor Economics (2002), died at his home in New York City on August 20, 2006 after a long illness. This brings to a close a long and productive career of a remarkable man.

The Formative Period

Mincer was born in Poland in 1922 and at the youthful age of 16 entered a Technical University in Brno, Czechoslovakia (Mincer, no date). His studies were soon interrupted by the invasion of Czechoslovakia in Spring 1939, and he spent much of the World War II years in various prisons and concentration work camps. After the war, his skills in several languages secured him a job working for the American Military Government in Germany. In 1948 he received a Hillel Foundation scholarship for exceptional survivors and a U.S. visa to resume his studies at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. Credit earned from placement examinations at Emory University enabled him to graduate in two years, after which he went to the University of Chicago to study economics.

|

|

Jacob Mincer met his wife Flora in Chicago. They went to New York in 1951 where she entered a hospital residency program and became a radiation oncologist. The Mincers had three children – two daughters and a son. Flora interrupted her career when the children were young.

Except for visiting appointments at the University of Chicago and a Fulbright Fellowship in Sweden, Mincer’s career centered on New York City. He completed his doctoral studies at Columbia University (1957), and taught at the City College of New York until joining the Columbia University faculty in 1959. The other institutions that played a major role in his professional life were the New York office of the National Bureau of Economic Research and the Labor Workshop at Columbia University. His close working relationship with Gary S. Becker, both at Columbia University and the NBER in the 1960s, was noteworthy. Each has acknowledged the enormous debt that they owed each other (Grossbard, 2001, 2006).

The New Labor Economics

Mincer has been accurately described as a pioneer of the New Labor Economics, sometimes referred to as Modern Labor Economics. Labor economics had been dominated by the focus on institutions, such as trade unions, labor law and collective bargaining, and description rather than analysis. The New Labor Economics, pioneered by Jacob Mincer, Gary Becker and H. Gregg Lewis, among others, focused on the functioning of labor markets and used microeconomic theory and statistical (econometric) techniques to rigorously test hypotheses and measure the magnitude of effects.

From its beginnings, the New Labor Economics focused on human capital, the idea that important insights regarding human behavior can be obtained by viewing people as analogous to a form of capital. While this approach may seem obvious to young economists today, it was revolutionary in the 1950’s and 1960’s.

There were several basic principles that characterized Mincer’s methodological approach, from his PhD dissertation to his last publication in 2006. Mincer believed in Occam’s Razor, the principle that simple models were to be preferred to complex models. Although he was mathematically astute, he avoided mathematics for its own sake. He also had faith in the power of economic theory to explain human behavior – that is, that people acted as if they were engaging in utility maximizing behavior. He believed that economics was all about the choices or opportunities that people had. He also felt strongly, and expressed it often, that economic theory can tell you what might be, but empirical analysis was essential to know what is. It was not sufficient to just set out a model – it had to be tested using the best available data and statistical techniques. He did not believe that one test was sufficient; he was committed to testing the robustness of empirical findings.

Mincer’s 1957 doctorial dissertation, which served as the basis of his famous 1958 Journal of Political Economy article, “Investment in Human Capital and Personal Income Distribution,” was a pioneering study. It broke with the prevailing literature that emphasized stochastic and mechanistic models to employ a model of optimal investment in human capital.

Mincer’s most frequently cited work is his book Schooling, Experience and Earnings (1974). It delved much more deeply into the relationship between human capital, and in particular formal schooling and labor market experience, and the shape of the distribution of earnings, as well as the determinants of the earnings of individuals. It is here that he developed the relationship between earnings and labor market experience, as distinct from age. This was a key contribution to the human capital earnings function, a statistical technique that quickly became a standard tool in labor economics.

In addition to his pioneering research on investment in human capital and income distribution, Mincer was also a pioneer in research on the economic value of time and female labor supply. He recognized early in his career that time was an economic good, and that the value of time would affect behavior. His research on the value of time and the labor force participation of married women, which was first published in the early 1960s (Mincer 1962, 1963), has served as the theoretical basis for the enormous literature on female labor supply that would be published by economists over the next four decades.

Jacob Mincer met his wife Flora in Chicago. They went to New York in 1951 where she entered a hospital residency program and became a radiation oncologist. The Mincers had three children – two daughters and a son. Flora interrupted her career when the children were young.

Except for visiting appointments at the University of Chicago and a Fulbright Fellowship in Sweden, Mincer’s career centered on New York City. He completed his doctoral studies at Columbia University (1957), and taught at the City College of New York until joining the Columbia University faculty in 1959. The other institutions that played a major role in his professional life were the New York office of the National Bureau of Economic Research and the Labor Workshop at Columbia University. His close working relationship with Gary S. Becker, both at Columbia University and the NBER in the 1960s, was noteworthy. Each has acknowledged the enormous debt that they owed each other (Grossbard, 2001, 2006).

An Economist’s Economist

Mincer was fundamentally an empirical economist. He sought to understand the world in which he lived, and his life experiences helped shape his insights. Mincer has said that his interest in female labor supply, and his insights on it, was influenced by his wife’s career, and her movement in and out of the labor force in response to changes in the value of her time in home production and in the labor market. I recall that at his 1991 retirement party he was asked, how he got the insight regarding the distinction between age and labor market experience as they affect earnings. His answer was a typically terse Mincer response – he said it was based on his life experiences.

He became an Emeritus faculty member in 1991. Ironically, Mincer found that he had to retire two years earlier than the mandatory retirement age because as a precocious child his parents had to declare his age as seven for him to be admitted to school when he was only five years old.

In a sense, all labor economists today are the “students” of Jacob Mincer. He had a direct impact on labor economics through his own research, and an indirect impact through the research of his students, many of whom have themselves contributed substantially to the field. His reach as a teacher was enhanced by a meticulous writing style which was elegant and clear. His classroom students benefited from lectures that were well organized and clearly articulated. He was recognized as an outstanding teacher.

Mincer showed no interest in being in the public eye, even though he was deeply interested in empirical findings. As a result, his name never became a household word, except for the households of labor economists.

However, for five decades Jacob Mincer was an outstanding scholar and teacher. His impact as an economist has been monumental. He will be missed.

Barry R. Chiswick

Chicago, Illinois

August 30, 2006

|

|

| |

References:

Grossbard, Shoshana (2001), “The New Home Economics at Columbia and Chicago,”

Feminist Economics, 7(5), November.

Grossbard, Shoshana, editor (2006), Jacob Mincer: A Pioneer of Modern Labor Economics, New York: Springer, 2006.

Mincer, Jacob (no date), Memoir, photocopy.

Mincer, Jacob (1958), “Investment in Human Capital and Personal Income Distribution,”

Journal of Political Economy, 66, August, pp. 281-320.

Mincer, Jacob (1962), “Labor Force Participation of Married Women,” in H. Gregg Lewis, ed., Aspects of Labor Economics, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1962.

Mincer, Jacob (1963), “Market Prices, Opportunity Cost and Income Effects,” in Carl Christ, ed., Measurement in Economics, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Mincer, Jacob (1974), Schooling, Experience and Earnings, New York: Columbia University Press.

Mincer, Jacob (2006), “Technology and the Labor Market,” in Shoshana Grossbard, ed.,

Jacob Mincer: A Pioneer of Modern Labor Economics, New York: Springer, pp. 53-77.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|