| |

|

|

German Reforms Pay Off:

Labor Market Largely Unaffected by Crisis

|

|

|

IZA Proposes “Agenda 2020” to Achieve Full Employment |

PDF Download

While many western industrial nations are

battling with the consequences of the global

and financial crisis, the German labor market

has shown a remarkable resistance. The

expected rise in unemployment did not appear.

In fact, there are already signs that the

labor market will emerge unscarred from the

crisis as the economy picks up again. This

observation is in stark contrast to assessments

made only a few years ago when Germany’s

labor market structure was rightly

criticized as too rigid and inefficient. The

current stability must certainly not be attributed

to the policy measures implemented

during the crisis to support the economy

and save jobs. It is much rather the positive

result of the fundamental labor market and

social policy reforms known as “Agenda

2010”, which were initiated in 2003.

|

|

Against this backdrop, IZA is urging policymakers

to continue down the road of

reform in order to achieve full employment

by the end of the decade. This goal is ambitious

but not unrealistic. However, it can

only be reached if the success of the Agenda

2010 is built upon rather than calling it into

question.In a recent contribution to the IZA Policy

Paper Series, IZA Directors Klaus F. Zimmermann

and Hilmar Schneider provide a first assessment

of the Agenda 2010 and outline the

core principals of a new “Agenda 2020” that

would further stimulate the dynamic development

of the German labor market.

Agenda 2010: Successful formula for

security and flexibility

The labor market reforms of 2003 have

changed the way of thinking in German social

policy by introducing the principle of

“supporting and demanding”.

Generally speaking, this approach to the

problem has been proven right. Despite

its mechanical of laws and a hesitant pace

of reform, this new orientation of labor

market policy has been shown to be successful,

even in a relatively short period

of time. The abandonment of the policy

of rewarding non-work, the liberalization

of temporary work and the efficiency-enhancing

organizational reform of employment

administration have led to a reduction

of structural employment for the first

time in three decades.

The labor market reforms

have been accompanied

with consistent

corporate

restructuring efforts.

Unions have also set

the right priorities in

wage bargaining by giving

precedence to job

security. This in turn

has been rewarded in

the petering out of the

economic crisis.

|

|

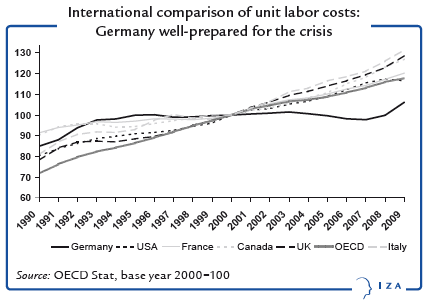

These measures have kept unit labor costs

in Germany virtually constant since the

mid-1990s while they have risen considerably

in the most important comparable

countries. All of which has resulted

in a substantial rise in the

international competitiveness

of German companies in recent

years.

The most striking progress can

be seen in the reduction in unemployment

by more than 1.4 million

since 2005. Even at the end

of the crisis year of 2009, unemployment

was at its second-lowest

since 1994; in the former East

Germany unemployment even

sank to its lowest level since reunification.

Employment hardly decreased

in comparison with 2008

and is still at a record level of over 40 million

employed individuals. This is all the more

remarkable because working hours have

been drastically reduced. The fact that this

has not resulted in a comparable decrease

of employment shows how highly businesses

value retaining their qualified workers.

This was undoubtedly helped by the rapid

expansion of short-time work with few

bureaucratic hurdles, which created an

enormous buffer. Many companies, however, have since then

returned to regular

employment. The number

of short-time workers

had nearly halved by

the end of 2009, following

the peak in May

of that year, without

having resulted in a

noticeable increase in

the number of unemployed.

|

|

The policy instrument

of short-time work has

thus fulfilled its purpose as a crisis buffer.

It is now time for a gradual return to

its “normal level” in order to discourage

companies from delaying structural adjustments,

which are independent of the crisis

(see also the next article in

this issue of IZA Compact).

Evidence of any positive effects of personnel

placement consultancies (Transfergesellschaften)

has yet to be shown. Funded

mainly by the Federal Employment Agency,

these organizations are meant to provide

laid-off workers with effective job search

assistance. For this, however, the employment

contract with the current employer is

ended in exchange

for a new, fixedterm

contract with

the placement consultancy

in question.

The workers

are de facto giving

up any job protection.

They can officially

remain with

the placement consultancy

for up to a

year. The model is

based on the idea

that job seekers

avoid being stigmatized

when they are

employed under the auspices of the consultancy;

and hence they are in a better position

to find new employment.

|

|

|

The only existing evaluation of placement

consultancies found them to be no more

effective than the Federal Employment

Agency. Hence claims for an expansion of

the placement model cannot be justified.

In particular, there is an underlying danger

that the period of unemployment benefit

entitlement can be abused. The supposedly

improved protection can easily bring

about the incentive to do exactly the opposite:

namely the active triggering of the risk

which was meant to be avoided.

|

|

|

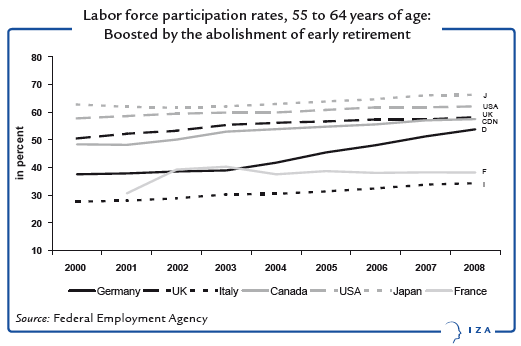

How closely the labor market is connected

to government regulations is shown particularly

by the rise in the labor market participation

rate of older people by

15 percentage points to 54% in

only five years. For decades it had

seemed as if an apparent declining

productivity of older workers

had been responsible for the decrease

in their employment opportunities.

We now know that

financial incentives often defined

the position of older workers in

the employment process. As long

as the welfare state actively promoted

early retirement options,

companies and employees made

ample use of it.

|

|

Since early retirement options

have been drastically restricted, either employees

or companies have themselves been

forced to bear the costs which arise from

an early exit from the labor market, which

they are evidently not prepared to do. This is

where the still very strong employment protection

legislation suddenly comes into effect,

a right which in the past many employees

themselves had willingly sold. As a result

companies have suddenly “discovered” that

their older employees are indeed still of use.

In the same breath, the myth that older

workers prevent younger ones from entering

the labor market has been shattered.

The labor market participation of 15 to

24-year-olds has also been increasing since

2003. The number of jobs in an economy

evidently is not a fundamental constant

which can be met with a redistribution of

work. The recent reforms have contributed

substantially to the rising rate of employment.

The introduction of Hartz IV abolished

many benefits, including unemployment

assistance. As a result the amount of benefit

can drop to the income support level

in as little as 12 months after becoming

Furtherunemployed.

The pressure

on those unemployed

to find a job as quickly as

possible has increased because

of this. This explains

not only a large part of the

labor market success but

also the political resistance

against the Hartz reforms.

The unemployed are prepared

to make greater concessions

to avert the threat

of income loss. The result

is that the unemployment

duration has noticeably

decreased and the proportion

of unemployed who

go from receiving unemployment

benefit type I to unemployment

benefit type II is clearly lower than before

when the process was from unemployment

benefit to income support. In this way unemployment

was actually halved, albeit

only among those who receive unemployment

benefit I. They are prepared nowadays

to accept jobs which they would not

have done under past conditions. This may

be regrettable, but it cannot be denied that

it is still better to accept a job which pays

less than the last one than to become longterm

unemployed.

|

|

The situation of the long-term unemployed

in Germany clearly demonstrates how important

it is to promote a greater willingness

to make concessions when searching for a

new job. Although the 2005 reforms have

improved the labor market prospects of

long-term unemployed, they have not wholly

succeeded in providing the exact help this

group needs. Short-term unemployment

has fallen considerably more

quickly than long-term unemployment,

which now accounts for over 50% of total

unemployment. Offers of further training

are insufficient in helping their plight.

Social justice requires reciprocity

The central problem of the German welfare

state is that low-wage work is not sufficiently

attractive. It is particularly true

of low-skilled workers that it is often not

worthwhile to be engaged in regular work

because the wages are often little more

than welfare benefits when unemployed.

The wages employers would have to pay for

menial labor to pay off bear no relation to

the market value of the service provided.

Empirical studies for Germany have shown

that the implicitly generated minimum

wage calculated in this manner is in the

range of 10 to 12 euros an hour gross.

A consequence of this is that Germany is

a world leader in do-it-yourself, and cash-rein-

hand work is on the rise. The extent of

the shadow economy can only be guessed.

According to recent estimates, it generates

one sixth of German GDP, which is equivalent

to six to seven million illegal jobs when

calculated proportionally to the number of

employed. The cause of the high unemployment

rate among the low-skilled can definitely

not be that there is too little work in

Germany.

There is currently sufficient employment in

the low-wage sector for those who do not

have any other employment prospects because

of a lack of qualifications. However, it

is a matter of making these jobs worthwhile. |

|

|

Benefit claims should generally be coupled

with an obligation for something in return

in the form of work in the broadest sense,

to which measures of further professional

and social training belong. This means that

benefits have to be “earned” one way or another.

This principle, also known as workfare,

creates strong incentives to work in

the low-wage sector for those people whose

qualifications are not enough to attain a

sufficiently high hourly wage in the market.

Workfare works

without lowering

the basic minimum

income level and

results in higher

income. Whoever

has the opportunity

to earn more

with menial work

than the minimum

income level has

an incentive to do

so. Workfare turns

benefit recipients

into taxpayers, and

thus helps to lower

public spending

and create more

leeway for future investments.

Furthermore, workfare prevents

companies from paying

low wages at the burden of

the welfare state.

|

|

|

An alternative that is still

being discussed in political

circles is a more generous

arrangement to earn

additional income when

claiming benefits. However,

this is just another

form of in-work benefit

that would generate substantial

windfall and an

undesirable subsidization

of part-time work.

Instead, policymakers

should focus on a gradual implementation

of the quid pro quo approach embodied

in the workfare principle. Also, in order

to create more equal opportunities, the

court-mandated revision of child benefits

should lead to a higher share of benefits

being paid in the form of vouchers.

|

|

|

Job centers:

More individual support needed

The top priority for job centers should be

that each customer is guaranteed one-stop

support with effective and custom-tailored

advice from one particular caseworker.

Strictly speaking, this would require the

creation of a wide-reaching federal organizational

structure. Early intervention and

support makes sense at the onset of unemployment,

especially for those in danger of

becoming long-term unemployed, such as

older, low-skilled or immigrant workers. An

independent organization should support

the whole process for these groups right

from the beginning, i.e., at the time of job

loss. Later, it should also take responsibility

for all other long-term unemployed. Only in

this way can structural unemployment be reduced once and for all. In addition, job centers

could be created which are independent

from local government and unemployment

insurance and whose task is to find work in

the most efficient manner, as is the model

in the Netherlands (where it applies to all

those unemployed). In this model the task

of finding work for these problem groups

would be taken away from the Federal Employment

Agency and the local administration.

In practice this would mean that the

current structure in place for advising Hartz

IV recipients would be dismantled, become

independent and be replaced with one with

expanded responsibilities and instruments.

Only in this way can we ultimately avoid the

collapse of effective support of job seekers

in a federal structure which works against itself.

The Federal Employment Agency could

confine its work to processing unemployment

insurance benefits and supporting the

short-term unemployed.

|

|

|

On the road to these changes, the existing

job centers can be improved by strengthening

the position of the caseworker. The caseworker

is the central figure at the job center

for a successful integration process and new

employment. Performance pay is necessary

for good caseworkers and counselors, as

is usual in other areas of industry; even in

the public sector the idea of a stronger link

between pay and performance is gaining

ground. In addition, benchmarking could

increase competition for performance and

competency among job centers. |

|

|

This help often comes too late for young

drop-outs, low-skilled workers, immigrants,

single-parent families and older recipients

of Hartz IV. Hence these groups often remain

dependent on state benefits for too

long, sometimes permanently. It is not only

about help in finding a job for these groups

with specific needs, but also about solving

diverse social conflicts, family problems, a

lack of motivation and qualifications, all of

which prove to be barriers to finding work.

Effective support tailored to individual

needs must be improved. Particularly single

mothers need more help not only to escape

from benefit dependency, but also to avoid

their children becoming the next generation

of Hartz IV recipients. Single parents with

children under age 18 make up about half of

all benefit recipients with children.

|

|

|

Moreover, it would make sense to grant

more non-cash benefits such as vouchers

for training and employment programs.

This would stimulate the market for certified

training providers, prevent the misuse

of benefit payments and improve the effectiveness

of qualification measures.

|

|

|

Educational reform, migration

and integration

The IZA strategy paper for labor market

modernization also contains recommendations

for the education sector. Knowledge

and skills are becoming increasingly

important as key resources for growth and

prosperity, all the more in the face of the

imminent demographic change. The parameters

of the labor market will drastically

change in the coming years compared to

the situation at the turn of the millennium.

On the one hand, there is an easing of the

labor market due to demographic changes

and the opportunities resulting from new

areas of employment; on the other hand,

there is growing financial strain on labor

through the burden of increasing social

security contributions. New employment

opportunities can come from this if politicians,

unions and employers react sensibly

to this process of change. Society and politicians

must be aware that education and

migration policies face especially difficult

challenges in light of a shrinking and aging

working population and the simultaneously

growing demand for human capital.

|

|

|

Even before the PISA study it was recognized

that the German education system

had to be put to the test. In the face of an

internationalization of labor markets, German

education institutes have fallen behind.

Compared internationally, childcare

facilities with qualified programs are too

few, educational outcomes have too great a

regional variance, the average time required

for school, training and university is too

long, and the proportion of workers with

no qualifications is still too high. All of these

show that the education factor is not being

sufficiently utilized as a key to the labor market.

To a certain extent it is also a failure of

the market, as the importance of education

and further training is not being recognized

early enough and, by international comparison,

human capital is not being sufficiently

rewarded. In a phase when using the available

knowledge most effectively should be

all that matters, allowing highly qualified

workers to emigrate to countries which offer

much more attractive working conditions is

a luxury Germany cannot afford.

|

|

|

The crucial foundation for cognitive and

non-cognitive development is laid in early

childhood. Family background should not

determine children’s opportunities later

in life. More autonomy and competition

between the schools will enhance performance;

student selection for the different

levels of secondary education should

occur at a higher age. The dual system of

vocational training, which combines classroom

learning with apprenticeships, can

be shortened. To avoid a financial entry

barrier to university education, tuition fees

could be financed by a graduate tax on employed

workers with a university degree.

|

|

|

Notwithstanding all the efforts at educating

Germany’s youth, the country is dependent

on the immigration of high-skilled workers

to combat the consequences of demographic

change and the growing shortage

of skilled labor. A selection system based

on economic criteria would significantly

increase the economic benefits of immigration.

Sustainable migration and integration

policies are a prerequisite of successful labor

market modernization and a major step

on the road to full employment.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |